Throughout time a lock of hair has been an intimate romantic token, a special keepsake, or even commemorative of important events and deeds. The incorporation of human hair in jewelry seems to have begun sometime during the Middle Ages and continued to increase in popularity through the years. Hairwork art and jewelry reached its zenith during the Victorian era, thanks to Queen Victorian favoring the fashion.

It is known that when her husband, Prince Albert, passed away, the queen wore a heart-shaped locket containing the prince’s hair over her heart. She also wore a bracelet with nine heart-shaped lockets, each of which contained a lock of hair from her children. She also gave a bracelet made of her own hair to Empress Eugenia of France. Hair generally doesn’t decay so these mementos were seen as lasting sentimental tokens.

An amazing array of jewelry was made from hair - brooches, bracelets, earrings, necklaces, rings, chains, watch fobs, cravat and shawl pins, and so on. Initially this jewelry seems to have been produced primarily by professionals. However, it eventually was viewed as a proper pastime for Victorian ladies and publications such as Godey’s Lady’s Book and Peterson’s Magazine offered “how to” instructions as early as the 1850s.

|

| An Expandable Bracelet |

|

| Hairwork bracelets |

Two Types of Hairwork

For both types of hair work, the hair would first be cleaned and treated for a few minutes in a solution such as hot water with ‘borax and soda.’ Once soaked, the hair would then be carefully scraped with a knife to make certain to remove any residue.

Early hairworks were very tiny, intricate designs created on a flat surface of china or glass called a ‘palette,’ thus, often referred to as ‘palette work.’ The design could be anything from a very elaborate miniature scene or a simply a single curl. If creating a scene, small hair clippings were ground with gum Arabic and painted onto ivory, china, or glass. Each design or picture was quite delicate and, therefore, sealed underneath a crystal cover or placed in a special compartment in a piece of jewelry. Some of the favored motifs were landscapes, weeping willows or tombstones (in mourning scenes), Prince of Wales ‘feathers,’ and basketweave patterns for backgrounds to lay hair designs on.

|

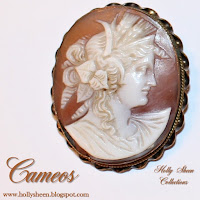

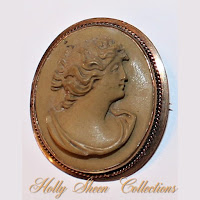

| Hairwork brooches |

|

These brooches contain no hair. Their basketweave backgrounds

are ready for hair to be inserted into the brooch onto the background. |

Later on, around the 1830s, another type of hairwork was developed. Referred to as ‘table work’ hair, it actually involved weaving the hair into lace-like, three-dimensional pieces that were quite springy and stretchy. A special table with a hole in the center was used to create this incredibly intricate jewelry. The hair was specially prepared, strands were counted, and then wound onto bobbins. The hair was then woven into patterns very similar to the method of making bobbin lace. Specialized fittings were added to the finished piece that allowed the hair jewelry to be worn.

|

| 3D hairwork brooches |

|

Hairwork necklace, necklace pendant, and two sets

of earrings |

Antique hairwork jewelry is now very desirable. You can collect old pieces or you can learn to make your own as Victorian ladies did.

|

These rings are matching "sister rings." The hair is inserted on the band.

The original owners had their initials engraved on the inside of the band. |

|

| Men's watch chains. |

|

| This ring has hair inserted on the band. |